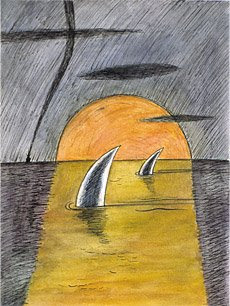

I visited the Lennon, Weinberg Gallery in Soho (it has since relocated to Chelsea) when I was eleven years old. Other installations were up, but they were of no concern to my mother or to Jill Weinberg who was showing us to the Deathship exhibition. For H. C. Westermann was my great-uncle and my mother had in the past two years inherited responsibility over his estate and artwork since his spouse, my mother's aunt, Joanna Beall had passed away. This was one of my first encounters with Cliff's work (his nickname and what he preferred to go by) as I had visited his amazing home in Connecticut earlier. It may seem like I'm bragging, but I have always been proud of being related, though not by blood, to him and though he was a difficult human being, like we all are, I feel his work has influenced me and will always do so. This series of sculpture and paintings had a massive impact on my perception of what art is. Until that time, I had always considered art a serious business. Though the topics of the exhibition were quite morbid and solemn, there was an element of playful detail to the works, especially seen in the Untitled (Death Ship) covered in dollar bills and The Kamikaze which twists the idea of kamikaze pilots on its head, where a ship dives towards an airplane in the middle of a desert landscape. These works were so important to understanding Cliff. They all came from his very real experiences of being a gunner on the USS Enterprise during the end of WWII and his witnessing a kamikaze attack on the USS Franklin. The memory of these Death Ships consumed him so that he sculpted and painted these watery coffins for about thirty years. There is very real tragedy to these pieces and strangely, what comes to mind is Breughel's Landscape with the Fall of Icarus, especially when paired with that last painting Death Ship in San Pedro. A battered and bloodied USS Enterprise lurches close to port, where on land a man walks by, rats scuttle past, and a noose like rope lies on the ground. The ship will never reach port and no one will come to receive it. It has been abandoned by those on land, for it carries death. In both of these paintings death occurs in the water, but this time the ship is the victim and not even many people are around to ignore it. Westermann was known for his surreal, violent, and often passionate landscapes. Where Breughel's piece holds some humor to it, Westermann's is hopeless, dark, and empty. But still with all of these pieces together in one room its hard to feel truly depressed. When I observed the works, I didn't understand the story and felt adrift in a watery graveyard of metal ships in wooden coffins. In my own work, I strive for this relevance of tone and content, but as well as the surreal and humorous nature Westermann's work possesses. His use of color is so odd; first it is subtle, then a moment or small object pops with some burst of color, like the lit window in the last painting. His breadth of materials is also stunning to me. Having seen other pieces at the MoMA or the Hirschhorn, his knowledge and mastery over wood, metal, and everything in between lets his work live and have a dynamic personality. I never met him and I am just starting to know him, but I feel in my heart he is a part of me like no other artist can be.

Westermann's work is wonderful! The man was brilliant!

ReplyDelete